Let’s face it, lying is a common feature of the human condition. Kids do it to avoid punishment. Politicians do it in service of their hidden agendas. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Corporations lie to us about product failures, hiding their internal data to forestall retribution. Governments? Yes, indeed. They call it propaganda. The archetype for lying, of course, is the used car salesmen. They’re notorious, right? After all, there’s a sucker born every second.

Deception is part of our everyday interactions; it surrounds us in the form of social niceties, misleading statements, wishful thinking, exaggerations, concealment, and flat untruths.

David Livingston Smith, “Why We Lie”

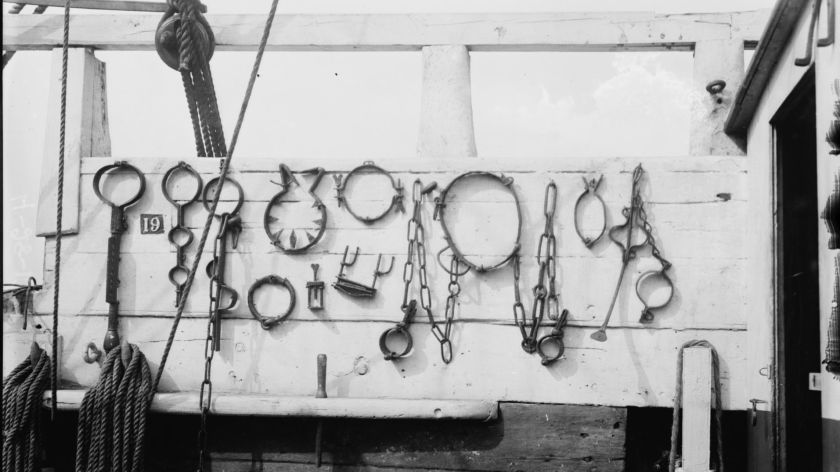

Arguably, lying has its worst consequences in the criminal justice setting. Because courts are in the business of identifying truth — at least to the point of determining whether someone is guilty of a crime — safeguarding that principle is a fundamental quest in all legal systems. We don’t always get it right. Twelfth century courts authorized torture as a way of obtaining confessions [1]. In Chicago in the late 1920s, the local method of “eliciting evidence [was] with rubber hose, black jack, and boot.” [2]

Lies in the Courtroom

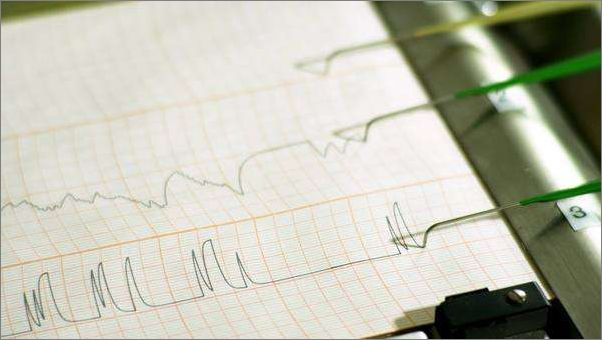

Reforms in the U.S. led to a softening of those approaches, at least overall. In the courtroom, lying became a punishable offense, called perjury. Police introduced the polygraph to combat deception. Its ultimate veracity is still in question.

American courts use witness cross-examination to ferret out deception. r, failing that, to impeach witness testimony. It is notable here that in this adversarial model, both sides use an edited version of “reality,” choosing only to present “facts” that favor their side of the argument. The assumption that these adversarial proceedings are ideally suited to determine “truth” has its share of skeptics (including yours truly).

Neither scientists, engineers, historians nor scholars from any other discipline use bi-polar adversary trials to determine facts. . . In matters of importance, we want an active investigative body capable both of testing any credible hypothesis and of amassing evidence from any source relevant to them.

Gary Goodpaster, On the Theory of American Adversary Criminal Trial, 78. J. CRIM. L. & CRIMINOLOGY 118, (1987).

Pity the poor jurors tasked with sifting through the mess of a complex trial with only limited, “he said, she said,” tools to guide them. Who is telling the truth? Who is shading the truth? Who is flat-out lying?

Clues to Lying

There are, in fact, reliable cues to deception — but these are not the cues that people prefer to rely on.

“People tend to rely on stereotypic cues to decide whether others are lying: For example, certain body movements (e.g., shifting positions, gaze aversion) increase beliefs that someone is being dishonest and even police believe in those cues. It turns out, however, that many of these ‘suspicious’ behaviors occur as often in people telling the truth as in people lying. A comprehensive review of the literature on cues to deception shows that many of the body movement cues that people think reveal lying, such as pauses, shifting positions, lack of eye contact, and most types of fidgeting, do not, in fact, differ between liars and truth tellers.

“Differences are found, however, in how information is conveyed. Liars provide less compelling accounts than do truth tellers; the lies include fewer details, are less plausible, and make less sense. Liars use fewer gestures and seem more distanced from their stories. They also correct themselves less often than truth tellers.” [3] [4]

Whatever the scientific evidence, American juries are trained by decades of police procedurals on television. And they have their own built-in lie detectors, based on their (often) limited personal contact with criminal deception. Here we include factors such as the so-called “honest face.”

“Some infants are anatomically gifted with an honest-looking face; others are facially disadvantaged. The gifted have baby faces, and the disadvantaged look mature. Individual differences in perceived facial honesty carry forward over the lifespan and help explain why some people are more likely than others to be seen as telling the truth.”

C.F. Bond and DePaulo, Individual differences in judging: Accuracy and bias, Psychological Bulletin, August 2008

In other words, sometimes juries are just plain lucky when they get it right.

[1] Ken Alder, “A Social History of Untruth: Lie Detection and Trust in Twentieth-Century America,” Representations, Vol. 80, No. 1 (Fall 2002), pp. 1-33

[2] ibid, Adler

[3] Barbara A. Spellman & Elizabeth R. Tenney, Credible Testimony In and Out of Court, Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 2010, 17 (2), 168-173

[4] It is notable here that Larry Demmert, Jr. was criticized for changing (correcting) his story over time. There is a fine-line here: at what point does making (necessary) corrections slip into deception?

Excerpts from the unpublished original manuscript, “Sailor Take Warning,” by Leland E. Hale. That manuscript, started in 1992 and based on court records from the Alaska State Archive, served as the basis for “What Happened in Craig.”

Copyright Leland E. Hale (2020). All rights reserved.

Order “What Happened In Craig,” HERE and HERE. True crime from Epicenter Press.