May it please the Court, the State rests. With this traditional invocation, the State of Alaska tossed its cards on the table and turned the case over to John Peel’s defense team. With the Peel trial at its psychic midpoint, one trend was obvious: the longer the trial went, the less crowded the courtroom. Still, it had its share of regulars. None were more steadfast than the women known as the “Three Ladies” — Marcia Hilley, Fran Bezdicek and Carroll Mackie.

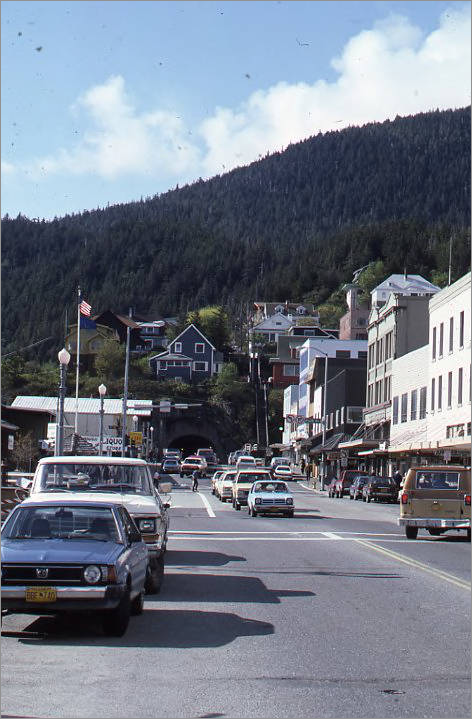

Of the three, Hilley and Mackie had known each other the longest; they had been best friends since attending Ketchikan High School 25 years previous. When Mackie’s children reached high school age, they formed a tongue-in-cheek club called I.S.P.Y. to keep an eye on them. Now that their children were older, I.S.P.Y. turned to other pursuits, like attending the Peel trial full-time. Mackie and Hilley had already started to reach some conclusions.

Halftime Score

For starters, neither Hilley nor Mackie believed Phillip Weidner’s assertions that John Peel was innocent. Part of that was due to their feelings about Phil Weidner, whom they characterized as a sleazebag who postured before the jury. They also noted with suspicion the relationship between the defense attorney and his client. Hilley thought that Weidner exercised near complete control of John Peel. Even on breaks, Peel said little. [1]

Their belief also depended, in part, on the State evidence that they’d heard — and the jury hadn’t.

- The statement of Jerry Mackie that John Peel looked like he’d been “caught with his hands in the cookie jar” when he spotted him in the Hill Bar.

- The assertion of Bruce Anderson that John Peel “looked amazingly like” the Investor skiffman.

- The testimony of the fisherman who said Peel was anxious to get out of town when he tried to sell him dope.

- The allegation that John Peel had failed his Bellingham polygraph test.

To their minds, the state had a stronger case than some realized. But what clinched it for them was John Peel.

He was so cold, as Hilley put it. Cold to anything that had been said in the trial up to that point. She saw him as cold to his mother, cold to his family. “It was always,” as Hilley put it, “like he was kind of not there. Here were all these people that were involved in this tragedy on his side, that were giving up their lives to be there, too, and Peel was just being so cold.”

On reflection, Hilley added, “maybe he had to be.”

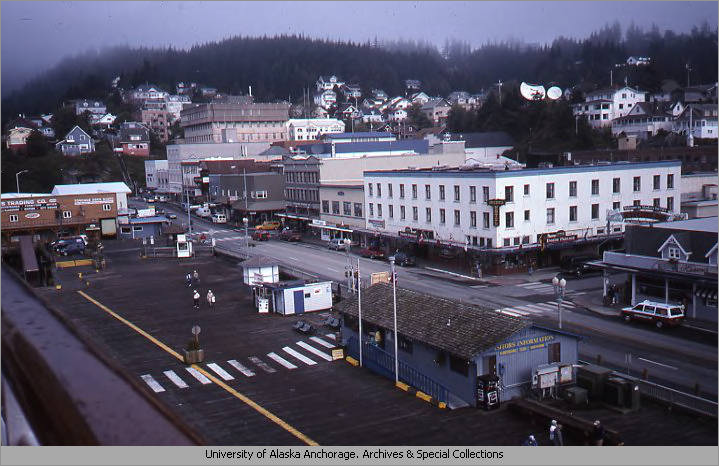

And though their informal poll revealed that most of the regulars agreed with them, not all the back benchers felt like Mackie and Hilley did. Here the small town side of Ketchikan showed itself most clearly. People had picked sides, and their feelings about guilt or innocence ran in the same direction.

Not Unanimous

One trial regular, retired Ketchikan High School teacher Bill Stefon, had befriended the Peel family shortly after John Peel’s arrest. He had visited John Peel in jail once a week for seven months. But what impressed Stefon was the conflicting, often contradictory, testimony given by some of the trial witnesses. He told a reporter he wanted to stop them outside the courtroom and say, “Hey, clue me in on what really happened.”

Marcia Hilley herself had a friend who felt sorry for the Peel family. She, too, had befriended them, showing her sympathy by bringing them cinnamon rolls. Soon, she was babysitting the Peel’s young son when Cathy Peel’s presence was needed in court. Hilley’s friend was just as convinced of John Peel’s innocence as Hilley was of his guilt — and couldn’t understand why Marcia felt the way she did.

Hilley started to realize that her friend was usually babysitting John Peel’s kid when the prosecution presented evidence that was “really against Peel.” That difference told Hilley she had information her friend lacked. So when her friend asked how she could feel the way she did, Hilley usually answered, “you should have heard what they said in court today.”

Just as routinely, her friend would reply, “Oh, no, no, no, you misunderstood.”

[1] Judge Schulz also believed Phil Weidner exercised considerable control over John Peel. It was particularly noticeable when Peel waived his right to testify at trial. Schulz remembered that he had to “be a little bit upset” to get Peel to personally enter the waiver, as the rules required. Phillip Weidner even wanted to put his own name on the record, instead of Peel’s.

Excerpts from the unpublished original manuscript, “Sailor Take Warning,” by Leland E. Hale. That manuscript, started in 1992 and based on court records from the Alaska State Archive, served as the basis for “What Happened in Craig.”

Copyright Leland E. Hale (2020). All rights reserved.

Order “What Happened In Craig,” HERE and HERE. True crime from Epicenter Press.